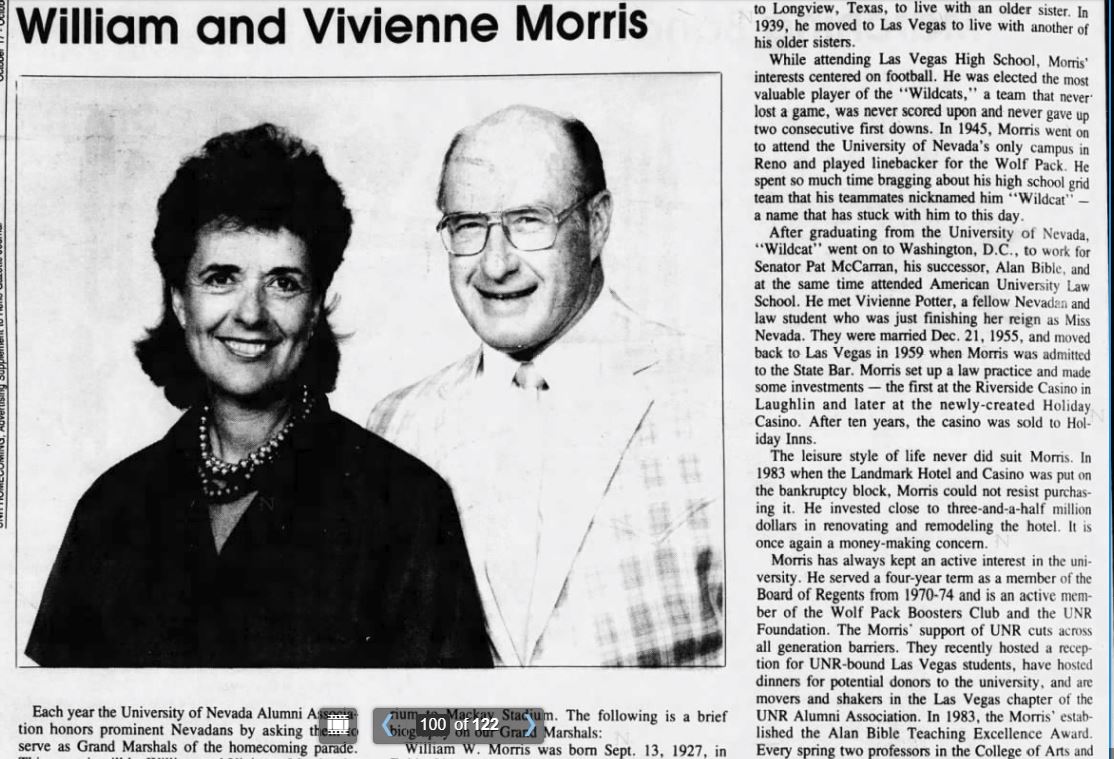

Photo by Dennis Connolly.

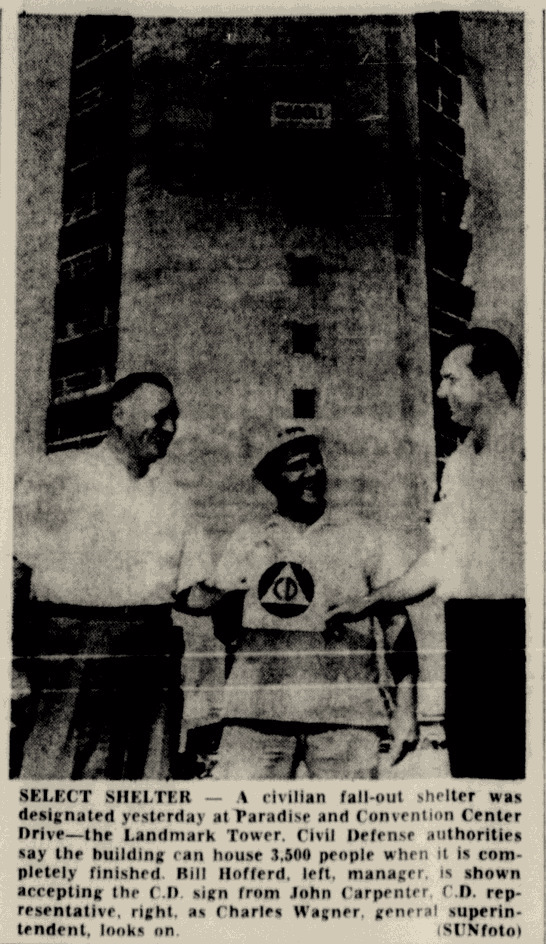

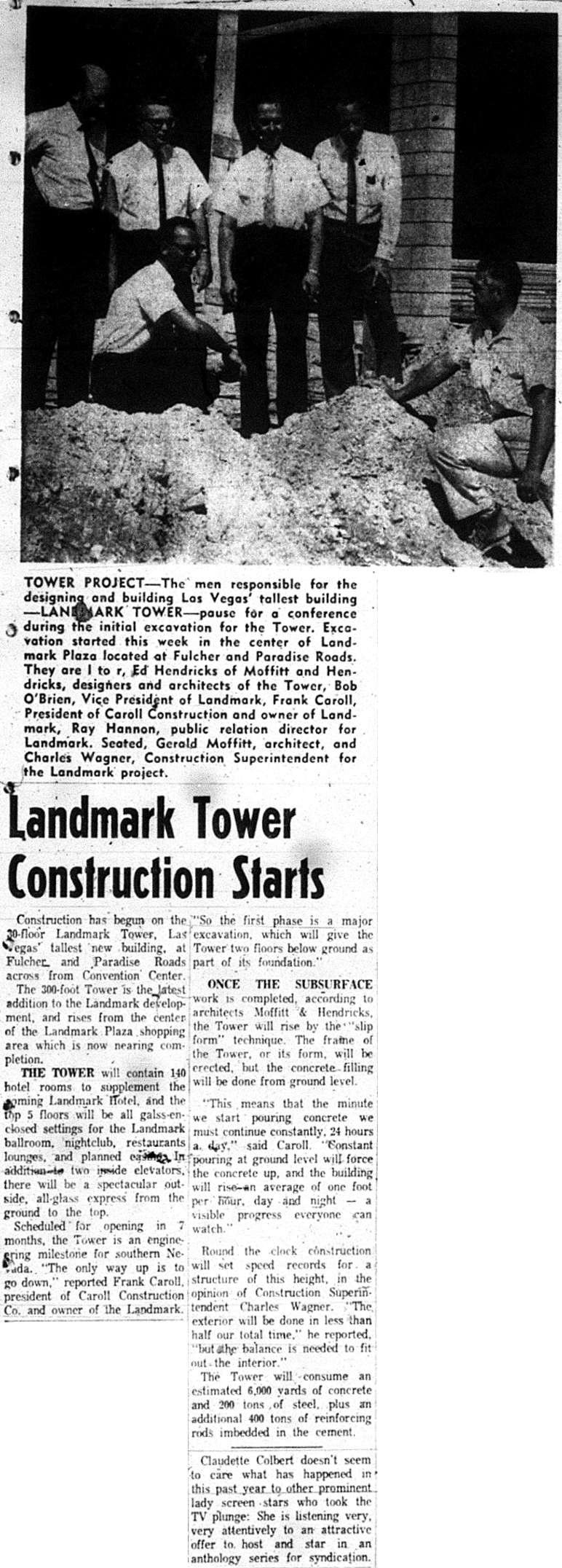

Things began to take a turn for the worse in 1963. With the ABCC looking for a return on its loan to Caroll and work on the tower halted, a new funding source was severely needed. Caroll began making the rounds in Vegas, looking for another partner who could finance the project to completion. He was having other problems at Landmark Plaza: Ralph Deligatti, owner of the Cozy Nook Restaurant, sued Landmark Plaza in April 1963 for breaking his lease agreement.32 Deligatti stated that the lease guaranteed no competing restaurants would be allowed to lease space at the Plaza. District Judge John F. Sexton awarded Deligatti $17,537 in damages. Caroll appealed the decision, countering that Deligatti failed to pay $1,800 in rent. However, because he filed his court paperwork late, the appeal was eventually dismissed on February 7th, 1964.33

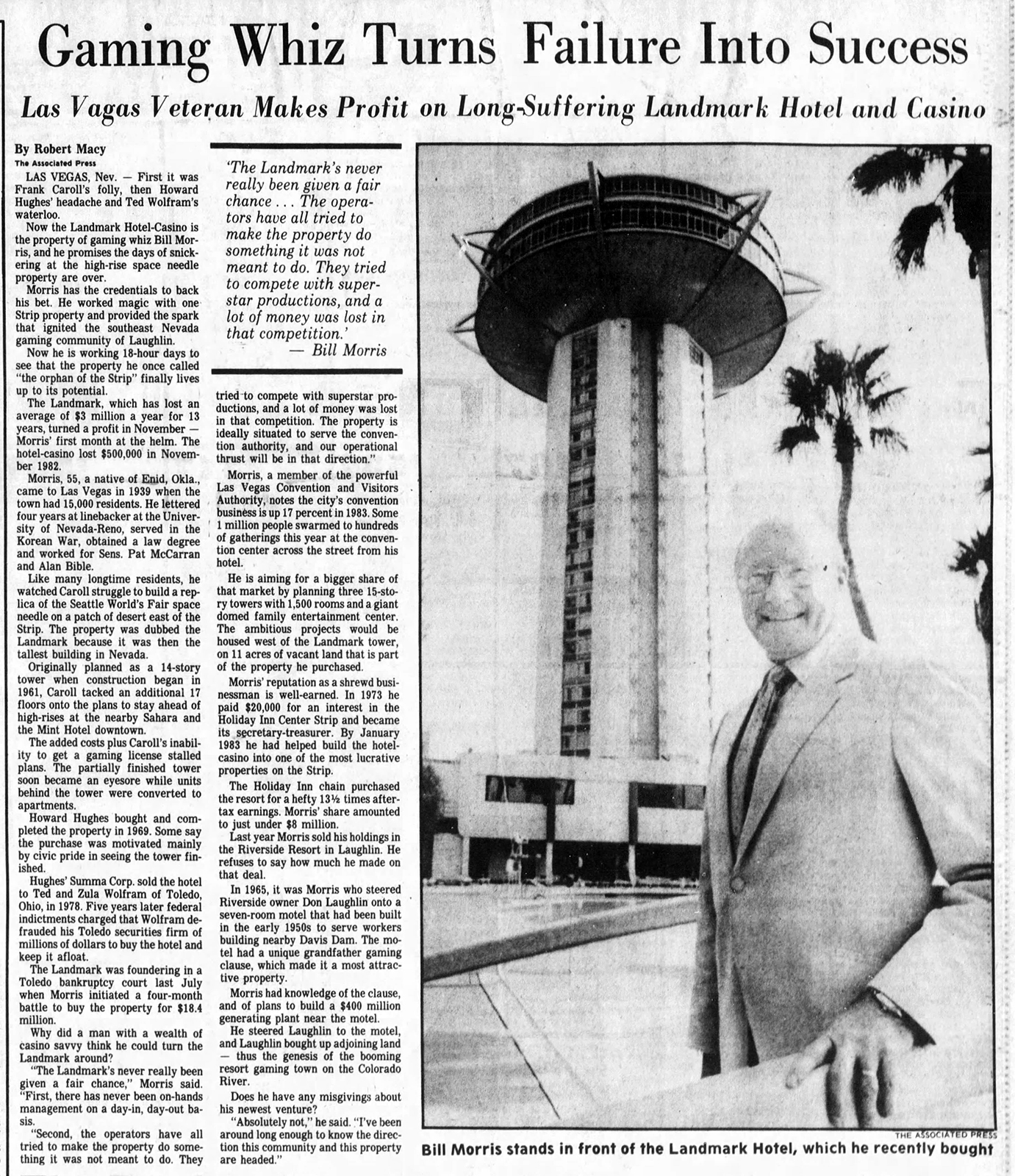

In May 1963, ABCC announced that it intended to sell the Landmark property on June 22 due to Caroll’s inability to make good on the loan.34 Caroll sued ABCC for $2.1 million in damages resulting from their withdrawal of funding, claiming that it agreed to finance the project to completion. Federal District Court Judge Roger D. Foley granted an injunction on June 17th, halting ABCC’s plans for sale until a trial could be held. ABCC, now having invested over $3.5 million in the project, argued that funds were secured by deeds of trust, which entitles them to foreclosure in the event of default.35 The matter went back and forth in court for the next fifteen months until October 5th, 1964, when a Federal court approved ABCC’s foreclosure on the property. The property, appraised between $8 and $9 million, was set to be auctioned on October 23rd.36 The tower was now called “Frank’s Folly” by residents.

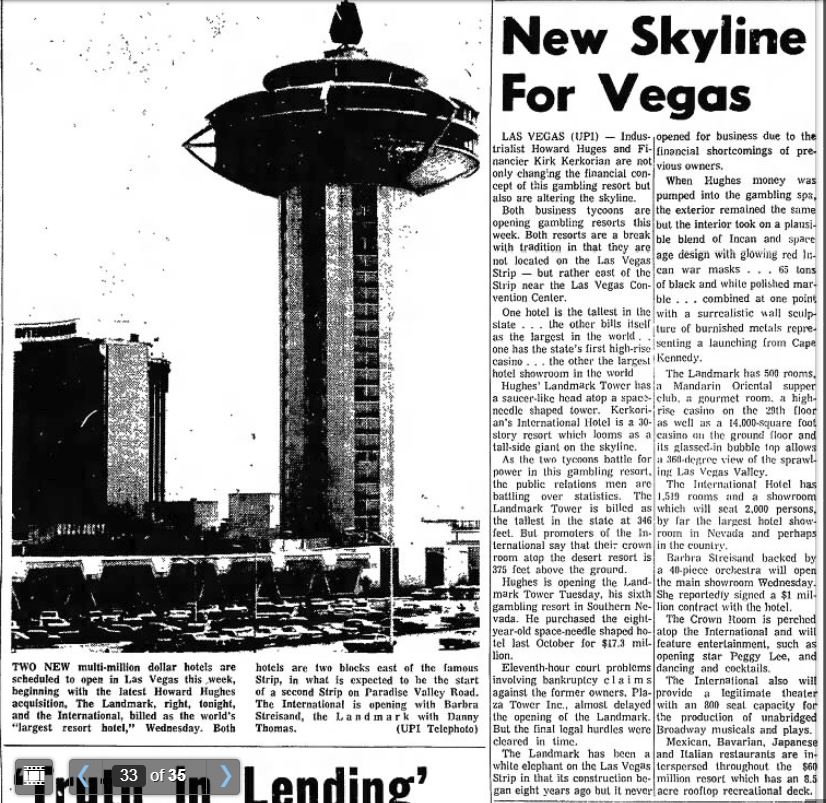

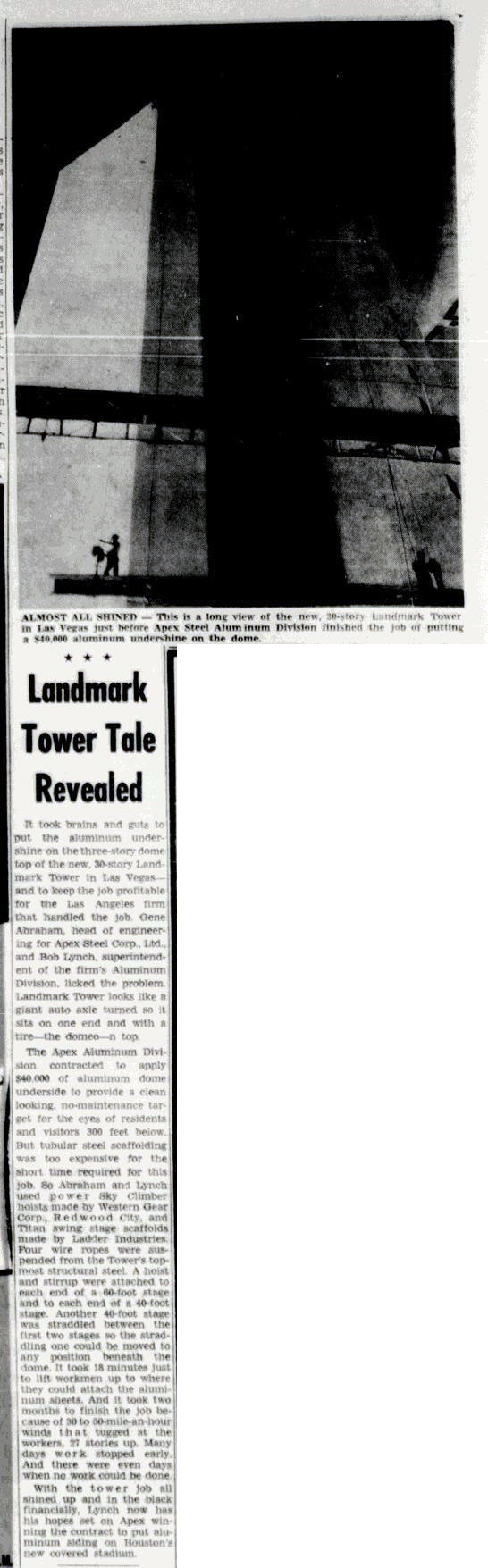

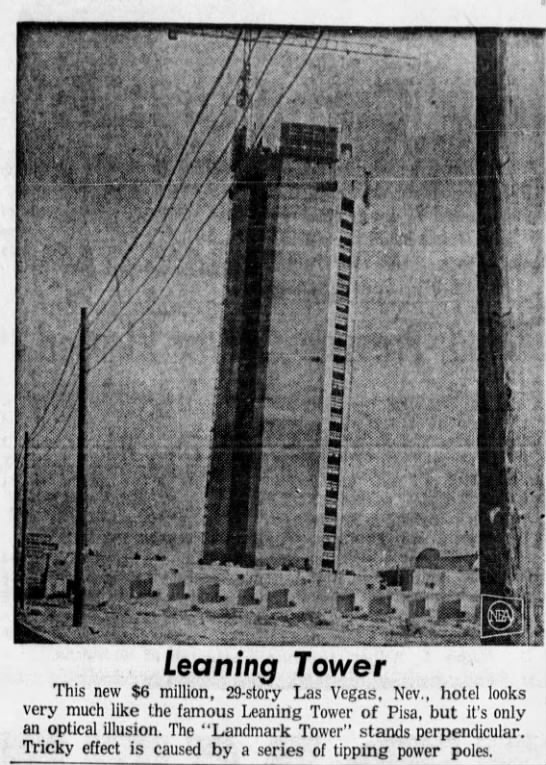

The tower was eighty percent complete at a cost of $5 million and still required six more months of work, which had stalled entirely. Gerald Moffett left the project, stating that Caroll had the plans changed so frequently he could no longer tell what the result was supposed to be.37 Attempts by RCA Whirlpool, which had assumed control of the property after foreclosure, to sell the Landmark were unsuccessful. At one point, a promoter wanted to use the tower for a parachute jump attraction, but RCA did not like the idea. In September of 1965, Inter-Nation Tower, Inc. began negotiations with RCA to turn the tower into an international marketplace to sell goods from around the world, but they fell through.38

Photo courtesy of the Las Vegas News Bureau.

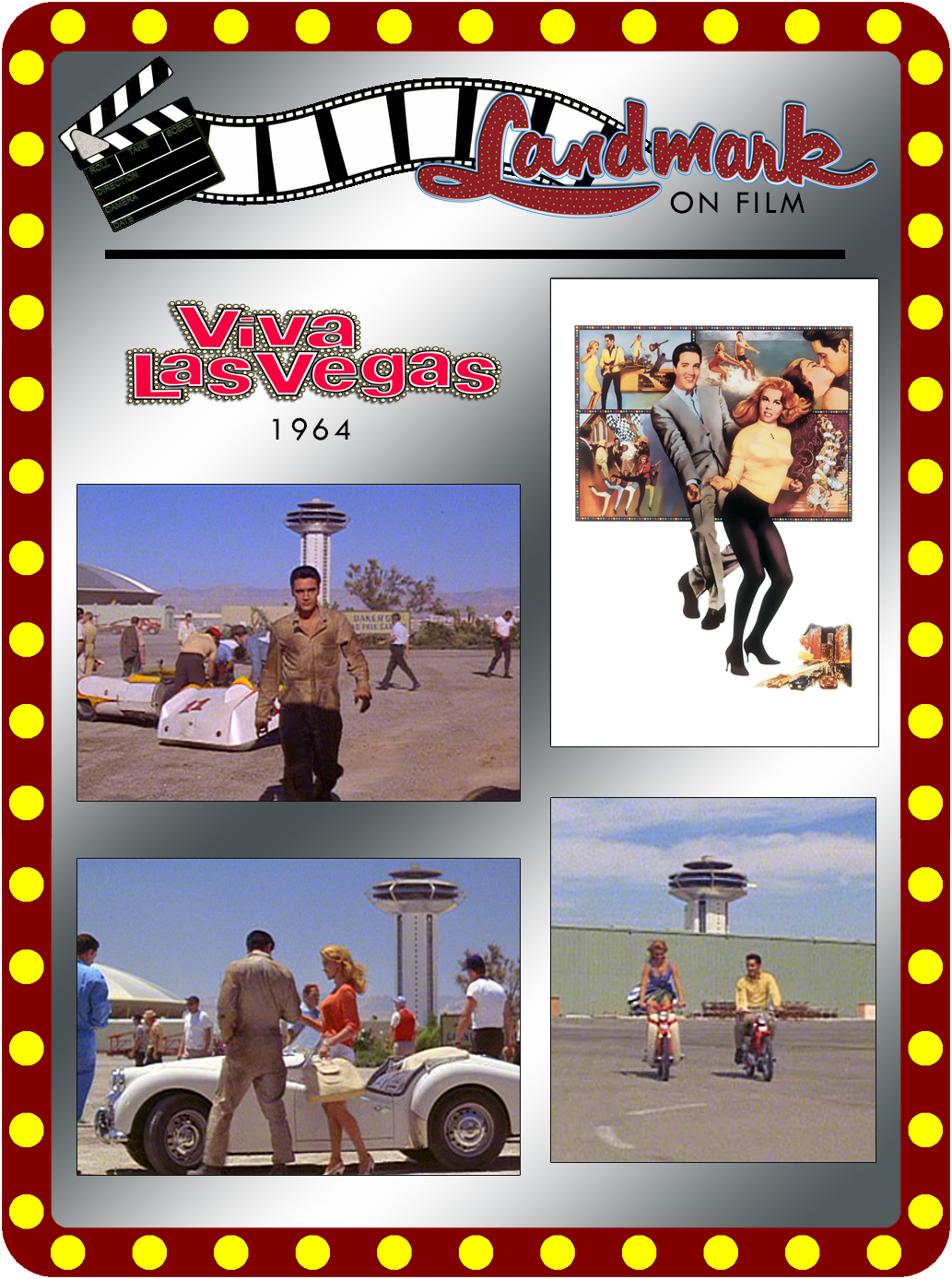

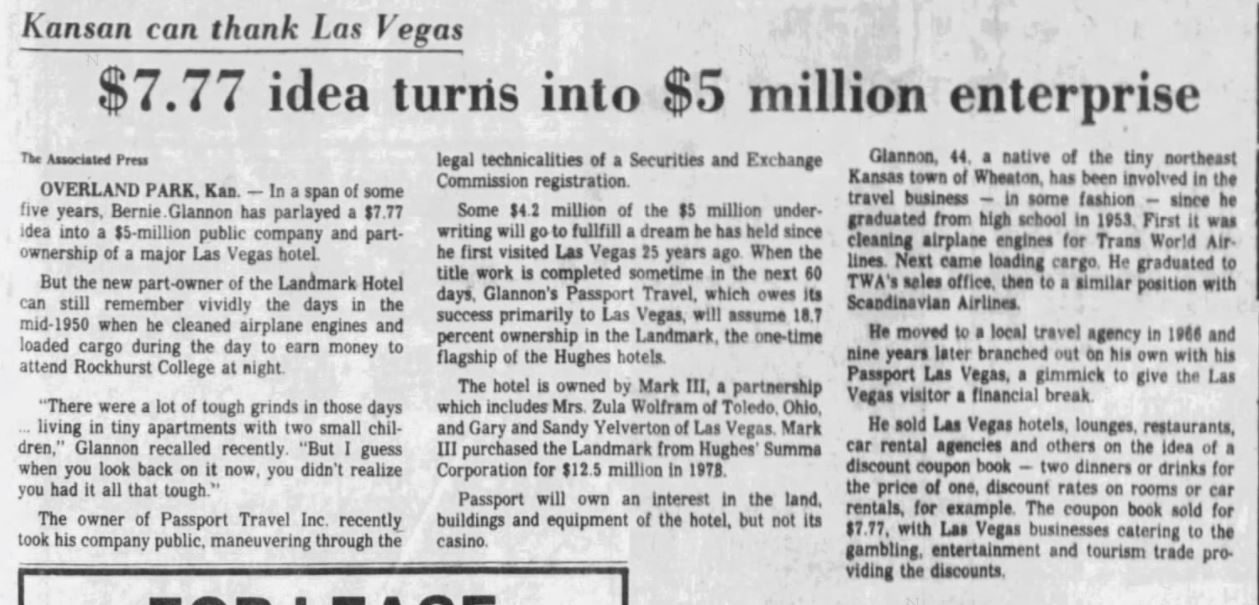

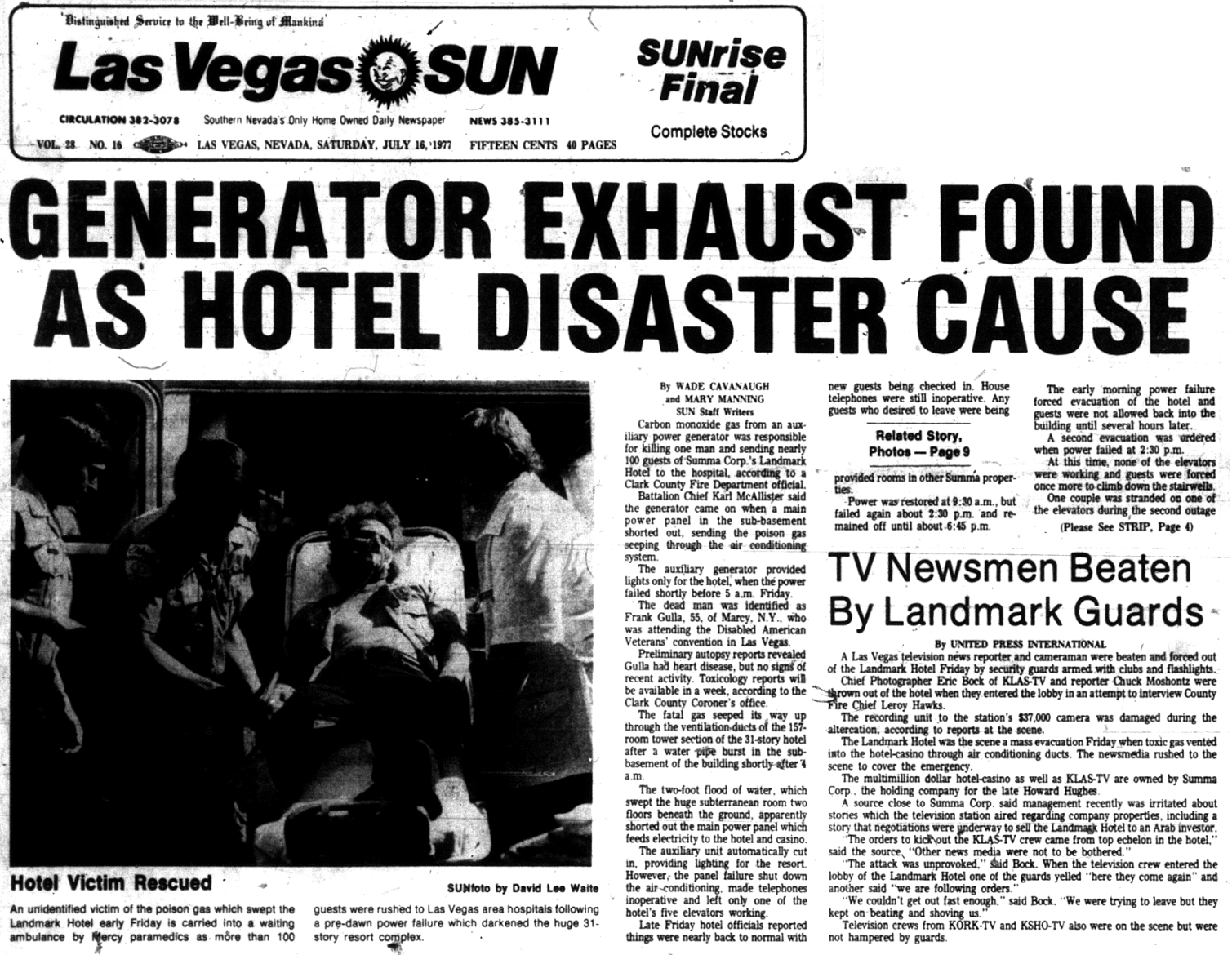

The Las Vegas Convention Center officials saw the incomplete tower as an eyesore that misrepresented the city’s growth potential.39 This was not the case as George Sidney, director of the Elvis Presley and Ann Margaret hit 1964 film Viva Las Vegas, featured the unfinished building prominently in the background of the movie’s key scenes, which was shot in Las Vegas in July of 1963. The first time we see Elvis appear, he is driving in with the Landmark behind him in the distance and framed perfectly within the shot, almost as if he is posing with it. Other scenes at this same location throughout the film always have the tower within the shot completely without the top being cut off. There is also a pivotal scene where the two main characters are riding motorbikes in the parking lot behind the Convention Center with the Landmark looming over the top of the building behind them. ![]()

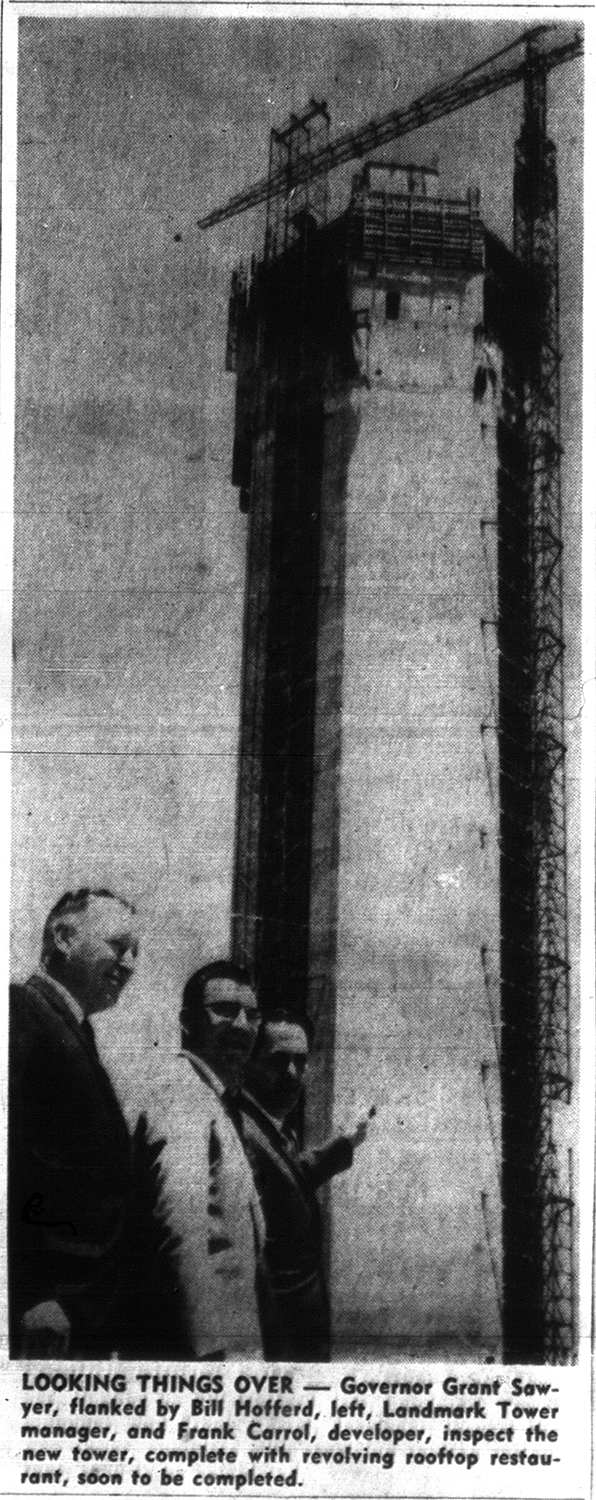

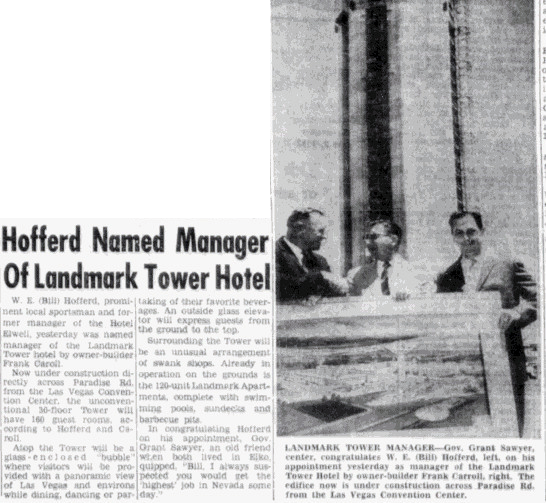

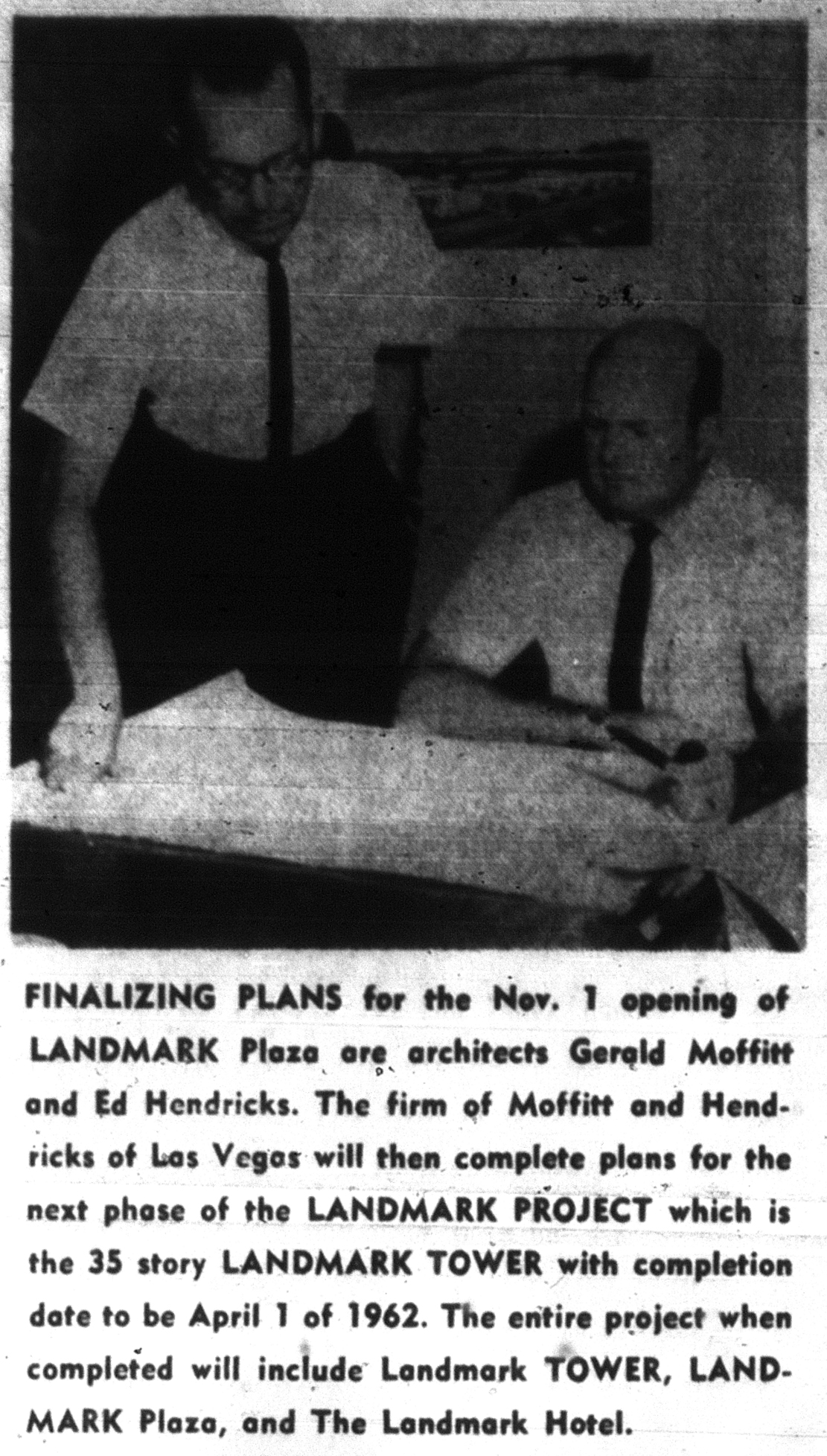

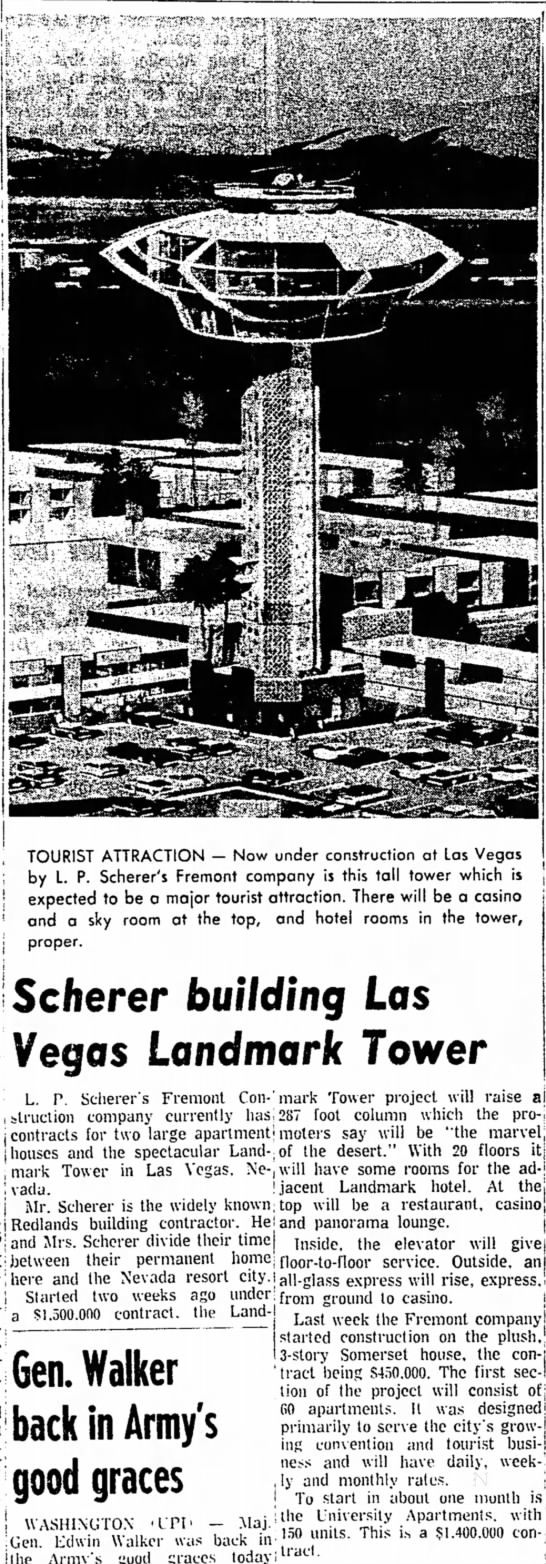

On May 1st, 1965, RCA began a series of surveys and measurements on the property in preparation for sale.40 Over the following year, they were unsuccessful in finding a suitable buyer. Frank Caroll and other investors, including Louis Scherer, entered talks with RCA on May 25th, 1966, to continue construction if financing could be acquired. Caroll began notifying tenants of Landmark Plaza that they may need to move out should financing be secured.41 In July, Scherer filed plans with the Clark County Building Department for the proposed tower completion while Caroll worked on the funding problem.42

Photo by Bernard Gotfryd, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

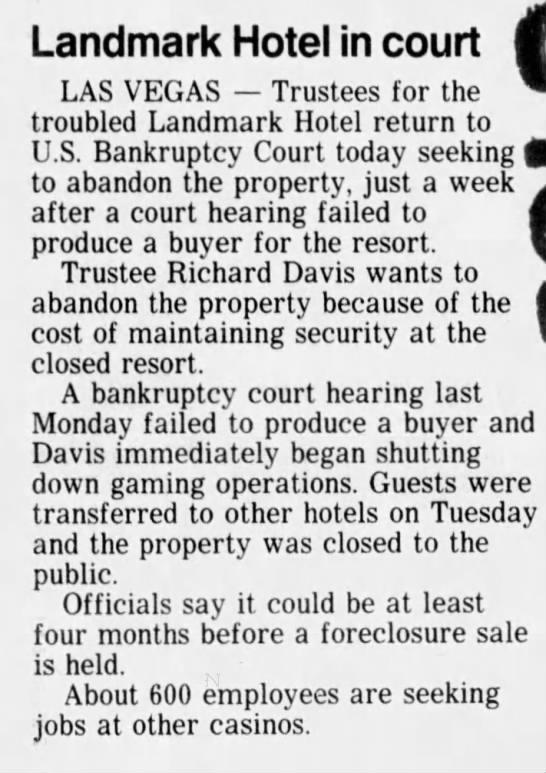

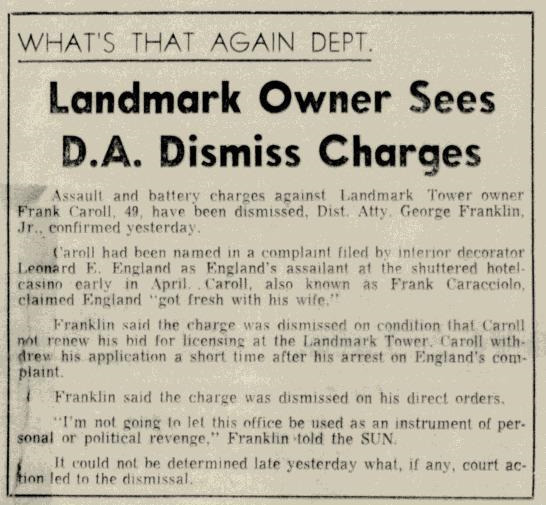

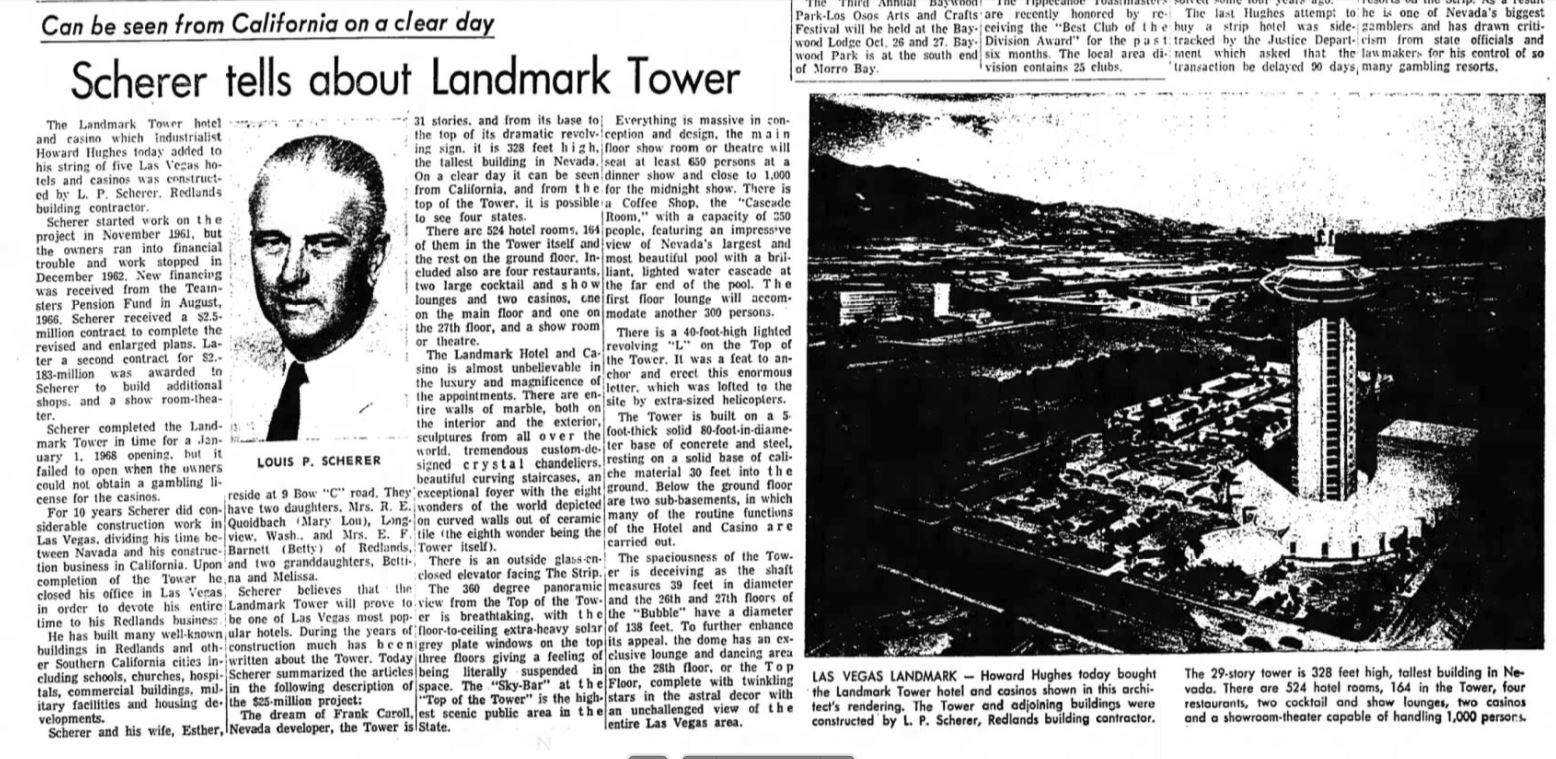

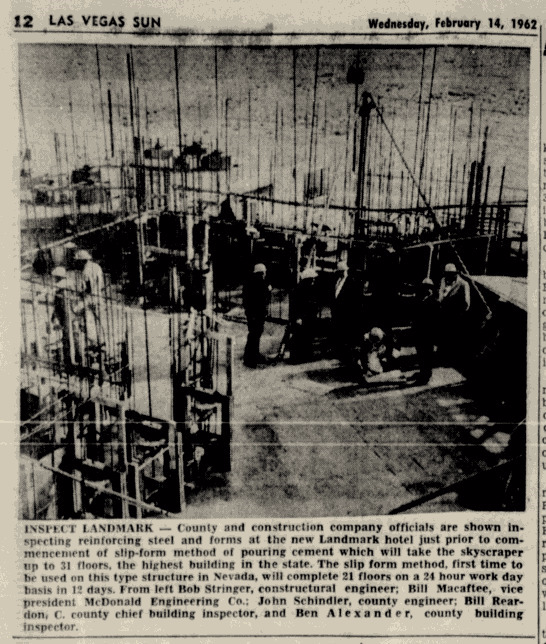

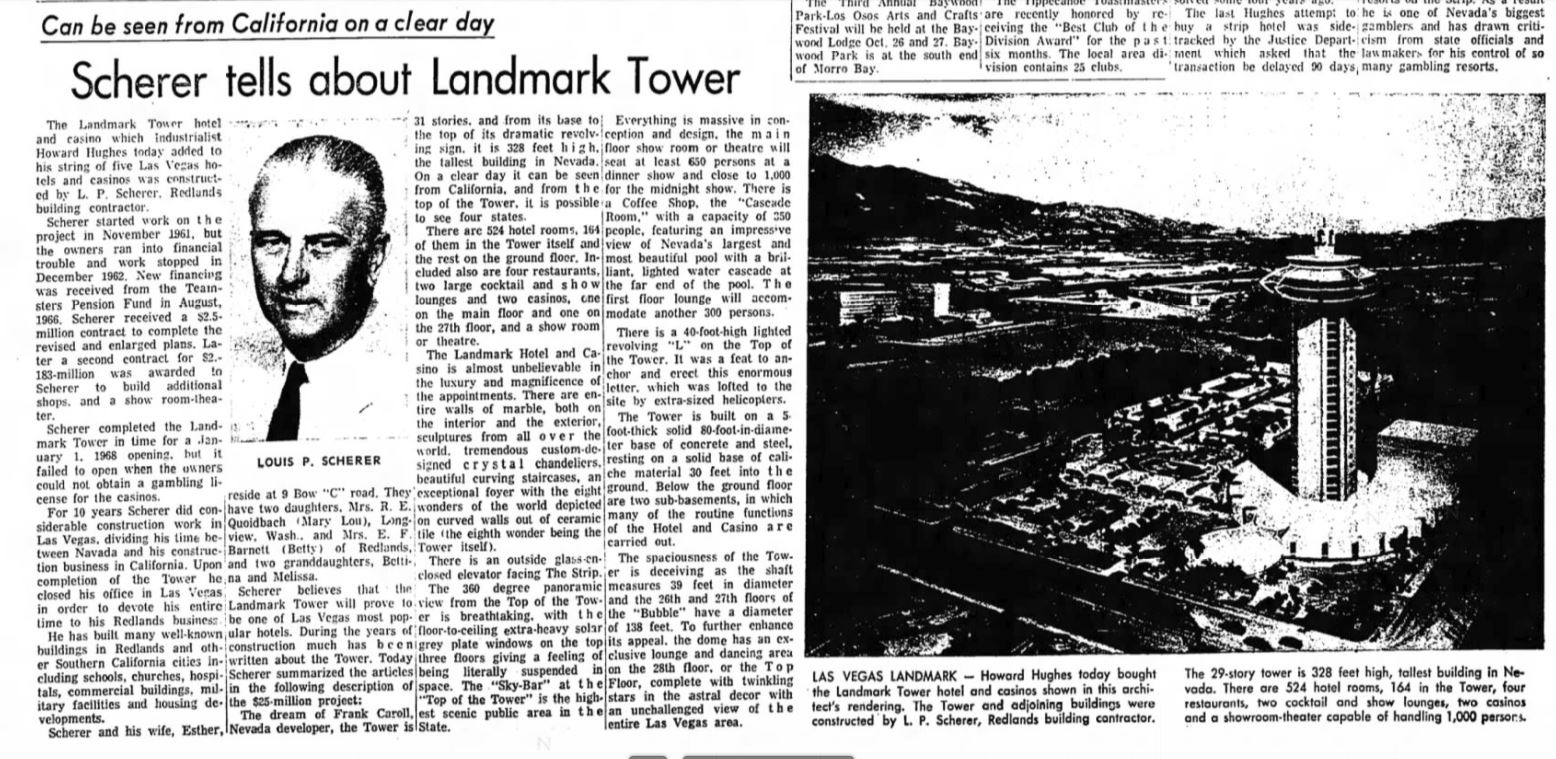

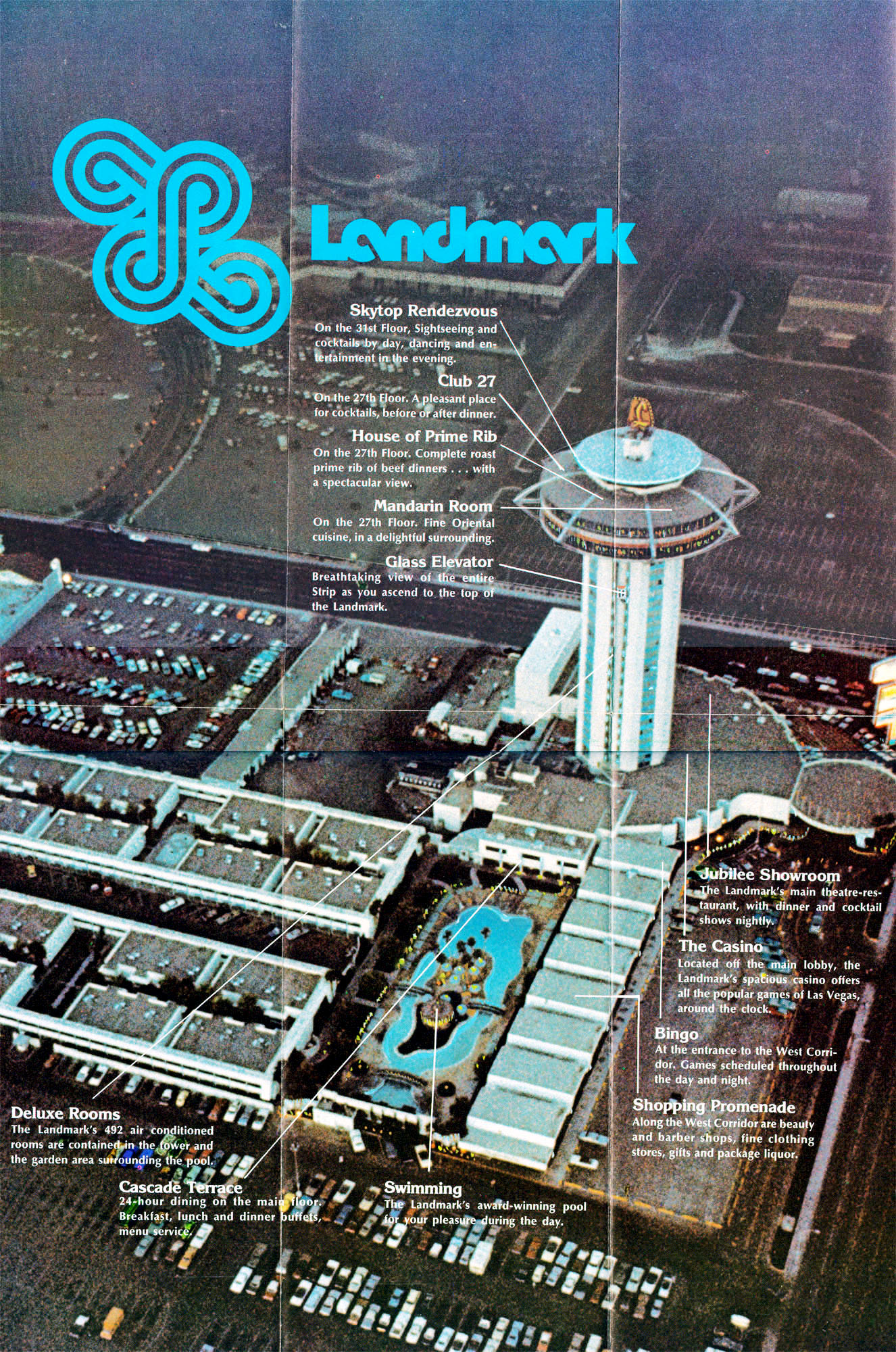

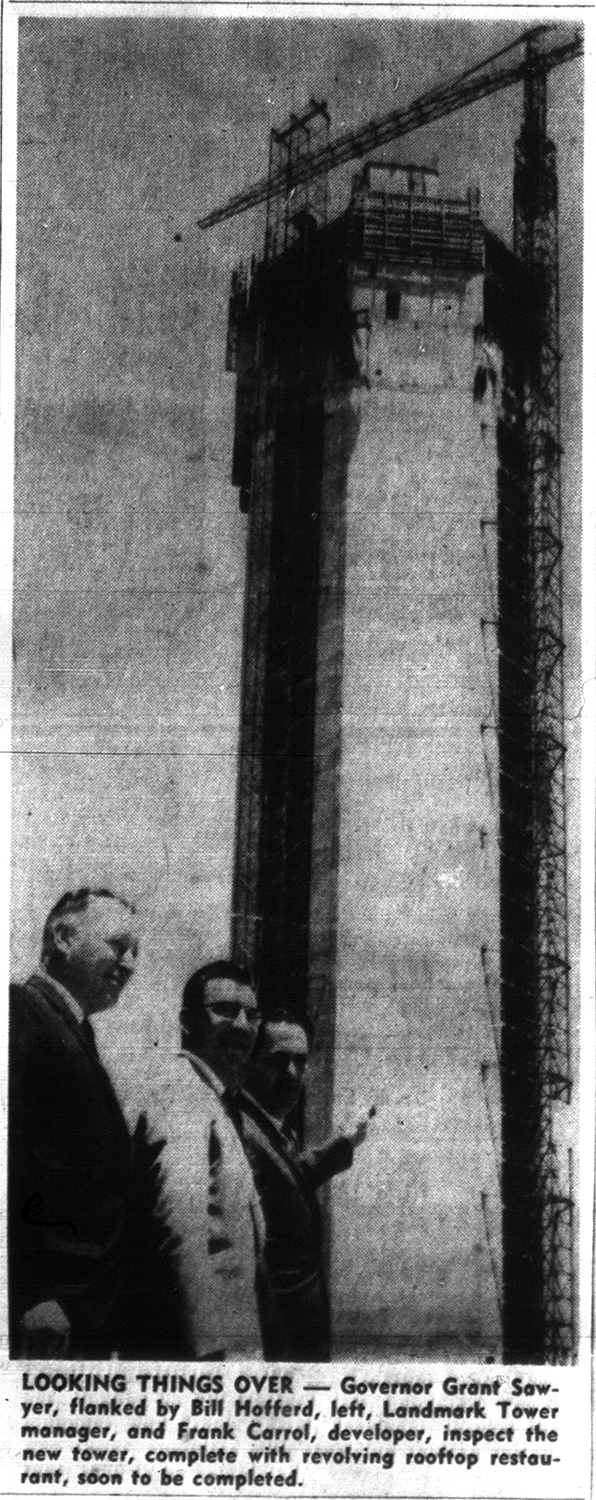

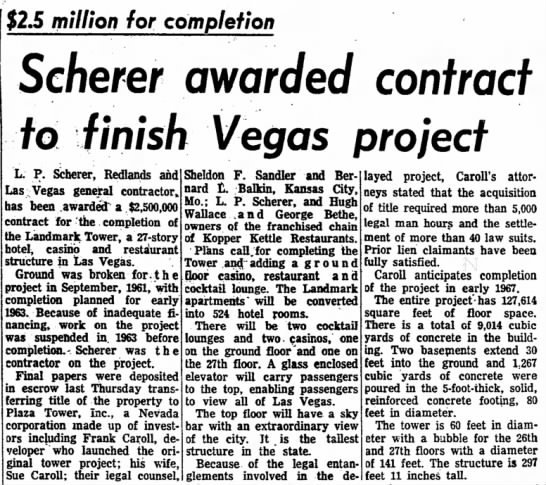

After negotiating a deal with the Central Teamsters Pension Fund, Caroll secured $5.5 million to complete the project on August 16th, 1966.43 Plans were made to eventually demolish Landmark Plaza for a ground-floor casino, pool, and a new indoor shopping pavilion. At the same time, the Landmark Apartments would be gutted and converted into garden-style suites for the new hotel. Caroll, his lawyers Sheldon F. Sandler and Bernard L. Daltin, Louis Scherer, and Kopper Kettle Restaurant owners Hugh Wallace and George Bethe formed Plaza Tower, Inc. They resumed construction on August 22nd, with completion expected in early 1967.44 Scherer’s Fremont Construction was awarded a $2.5 million contract to complete the tower and other facilities.

Plaza Tower acquired ownership of the property from RCA after more than 40 lawsuits were settled, totaling over five thousand person-hours of work on the part of Caroll’s legal team.45 Architects George Tate and Thomas Sobrusky were tasked with designing the new portions of the hotel.46 The gas station and Landmark Plaza were demolished, and in their place, a 14,000 ft2 47 casino was built around the tower and an adjoining restaurant, kitchen, and showroom.

Just as things were starting to improve, Caroll hit another roadblock on November 10th, 1966. He was appearing before the Clark County Gaming Licensing Board to request the ability to operate two slot machines in the Landmark Coffee Shop, which sold food to the workers on the site. Las Vegas Sheriff Ralph Lamb fought to block Caroll, citing an incident from years earlier where police were responding to suspicious activity at the Landmark Apartments. “There were several hoodlums hanging around Caroll’s apartments and when we went down there he ran sheriff’s officers off. He did that to me personally,” Lamb stated to the board.48 When Lamb implied that Caroll had intentionally hidden a hoodlum from police, Caroll countered that he took officers to the apartment and allowed them full access. Lamb was not swayed in his position and insisted, “This is a guy who has been uncooperative with the sheriff’s office ever since he came to Las Vegas.”49 The board decided to revoke Caroll’s gaming license entirely.

While the Landmark had been scheduled to open on September 15th, 1967, construction problems caused this date to be changed to November 15th. A grand opening celebration was planned for New Year’s Eve.50 Once again, Scherer’s Fremont Construction was awarded a contract to complete portions of the project. This time, it was for the pool, shopping corridor, and remaining facilities for $2.183 million.51 Extra heavy solar grey plate windows were installed in the tower, and the Landmark Apartment buildings were gutted for conversion into suites.52

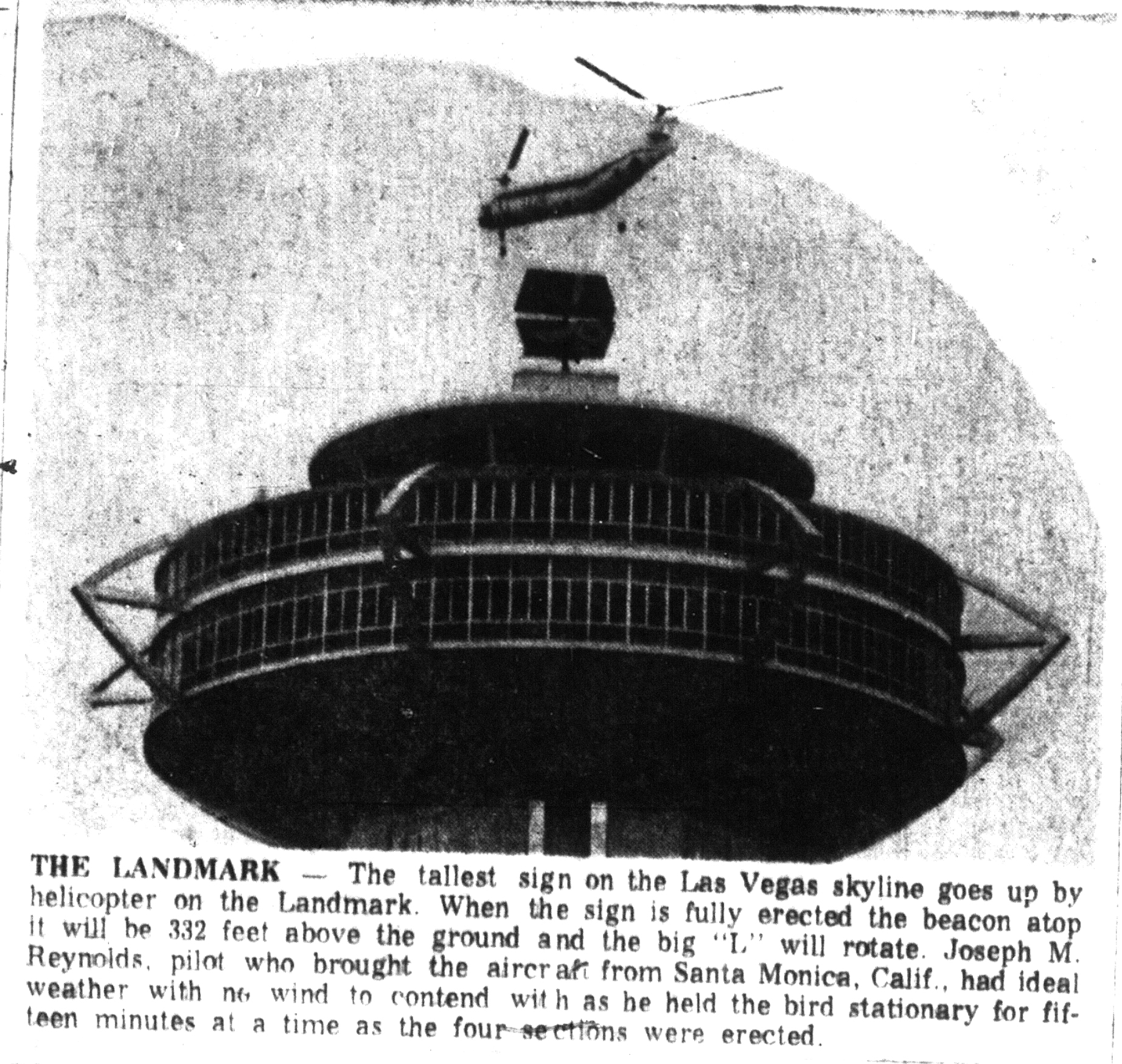

Even with the delays, construction pushed along. On November 18th, the Landmark’s iconic 40ft tall revolving “L” sign was installed. It comprised four sections, which had to be carried up one at a time by a Piasecki H-21B Workhorse helicopter operated by Briles. It was number N9719Z.53

Footage provided by Darla McDowell.

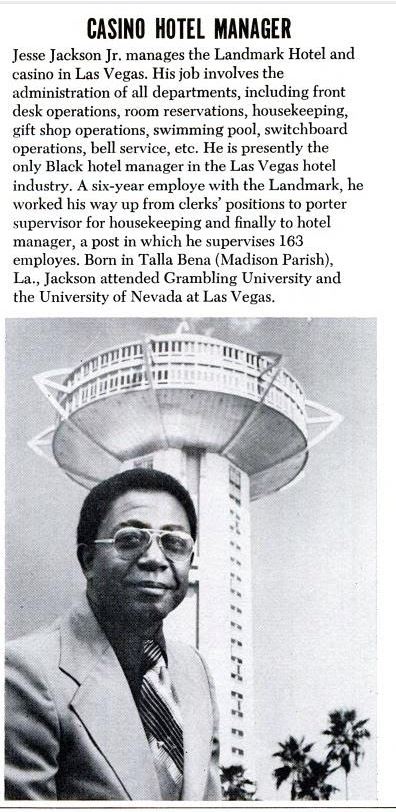

With the hotel finally reaching completion, Caroll made another bid for a gaming license in December of 1967.54 A backlog at the Clark County Gaming Licensing Board caused investigation delays that required approval. As of the following March, a decision was expected to be reached by May. By this time, operations had been split between two companies. Plaza Tower, Inc. would own the land and receive rent and casino profit percentages for Caroll (95%) and Sheldon Sandler (5%). Landmark Hotel and Casino would operate the facility with an interest split between the vested parties, including Caroll as CEO (56%), Louis Scherer as secretary-treasurer (12%), and Richard E. Parker as executive vice president (1%).55